Each year, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) measures the availability of rental housing affordable to extremely low-income households and other income groups. Based on the American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS), The Gap presents data on the affordable housing supply and housing cost burdens at the national, state, and metropolitan levels. The report also examines the demographics, disability and work status, and other characteristics of the extremely low-income households most impacted by the national shortage of affordable and available rental homes.

Who Are the Lowest Income Renters?

Of the 45.1 million renter households in the U.S., 11.0 million have extremely low incomes – that is, incomes at or below either the federal poverty guideline or 30% of the area median income (AMI), whichever is higher.

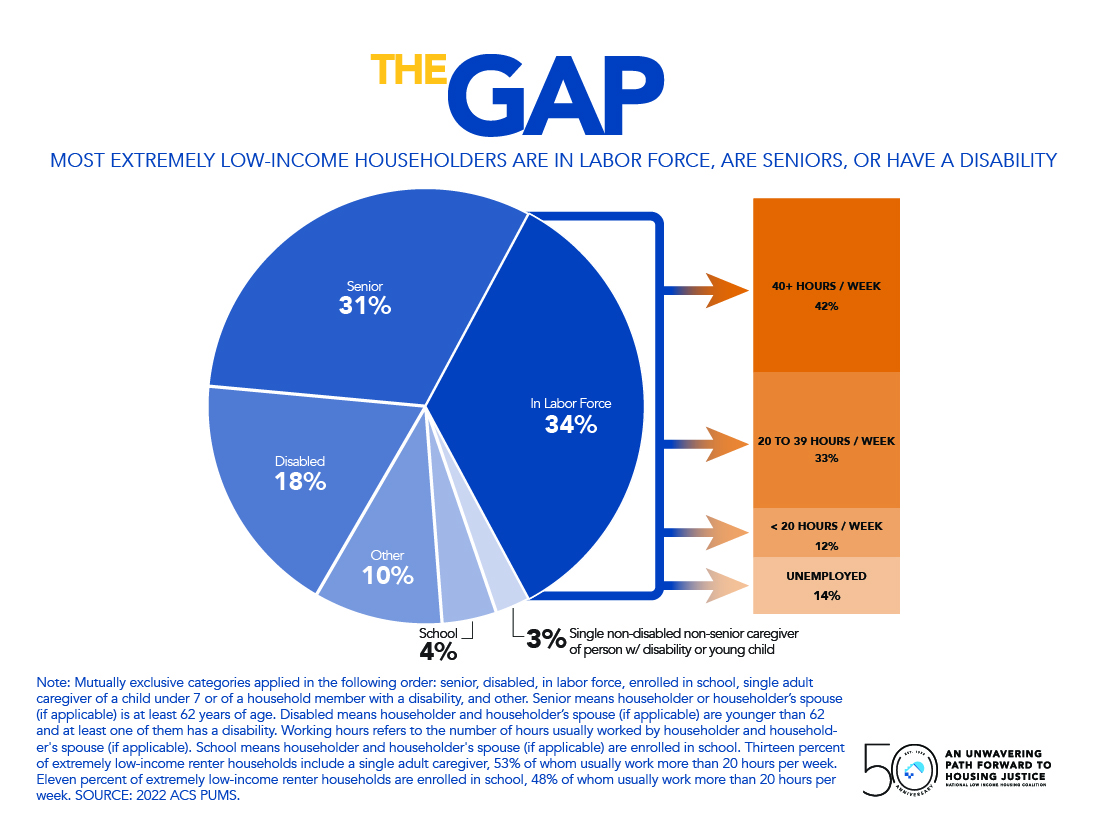

Forty-nine percent of renter householders with extremely low incomes are seniors or householders with disabilities. Another 41% are in the labor force, in school, or single-adult caregivers of school-aged children or family members with disabilities. Of those in the labor force, 42% usually work 40 or more hours per week.

The shortage of affordable and available rental homes disproportionately affects Black, Latino, and Indigenous households, as these households are both more likely to be renters and to have extremely low incomes. Black households are more than three times and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native households more than twice as likely as white households to be extremely low-income renters. Nineteen percent of Black households, 16% of American Indian or Alaska Native households, and 13% of Latino households are extremely low-income renters, compared to 6% of white households. This disparity is the product of historical and ongoing injustices that have systematically disadvantaged people of color, contributing to lower homeownership rates, income, and wealth accumulation.

There Is a Severe Shortage of Affordable Housing for the Lowest-Income Renters

The U.S. has a shortage of 7.3 million rental homes affordable and available to renters with extremely low incomes. Only 34 affordable and available rental homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. The shortage of affordable and available homes for extremely low-income renters impacts all states and the 50 largest metro areas, none of which have an adequate supply for the lowest-income renters. Among states, the supply of affordable and available rental homes ranges from 14 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households in Nevada to 57 in South Dakota. Thirty-five of the largest 50 metros have fewer than the national level of 34 affordable and available units for every 100 extremely low-income renters.

The Shortage of Affordable Housing Results in Cost-Burdens and Housing Instability for Millions of Renters

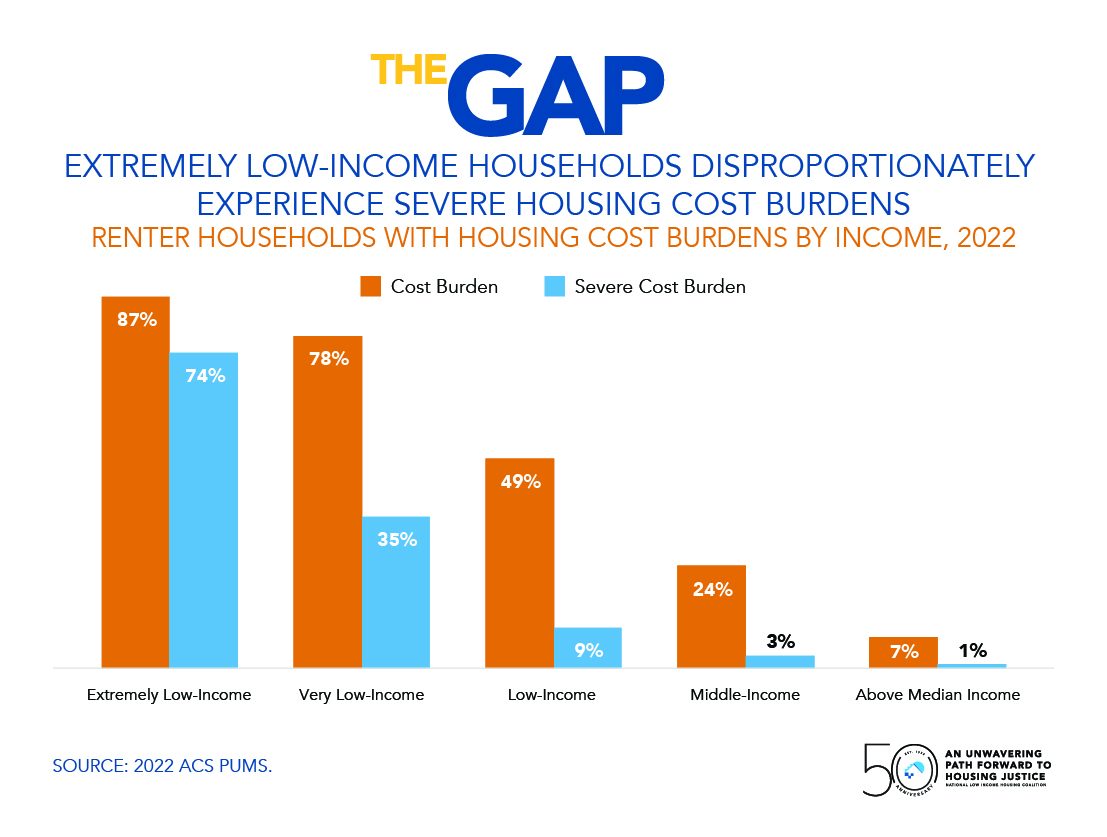

Cost burdens are a direct result of low incomes and the shortage of affordable and available rental homes. A household is cost-burdened when it spends more than 30% of its income on rent and utilities and severely cost-burdened when it spends more than 50% of its income on these expenses. Eighty-seven percent of all extremely low-income renters experience some degree of cost-burden, and 74% are severely cost-burdened. They account for 69% of all severely cost-burdened renter households in the U.S.

Severely housing cost-burdened and extremely low-income renters make significant sacrifices to pay for housing. An extremely low-income family of four with a monthly income of $2,500 paying the average two-bedroom fair market rent of $1,486 spends nearly 60% of their income on rent and has only $1,014 left each month to cover other expenses. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) "thrifty food budget" for a family of four (two adults and two school-aged children) estimates a family needs to spend $969 per month to cover food alone, leaving only $45 for childcare, medical care, transportation, and all other necessities.

The Worsening Shortage of Affordable and Available Rental Housing

Between 2019 and 2022, the shortage of affordable and available rental homes for extremely low-income renters worsened by nearly 500,000 units, increasing from a shortage of 6.8 million to 7.3 million.

Long-Term Needs

To fully address the shortage of affordable rental housing for renters with extremely low incomes, Congress must significantly increase federal investments in programs that both preserve and expand the supply of deeply affordable units and bridge the gaps between incomes and rent. The “Housing Crisis Response Act” (“H.R. 4233”), for example, would provide $150 billion for key affordable housing programs, including $65 billion for public housing, $15 billion for the national Housing Trust Fund (HTF), and $25 billion for housing choice vouchers (HCVs). Meanwhile, the “Ending Homelessness Act of 2023” (“H.R.4232”) would establish a universal voucher program that would enable all eligible households to receive rental assistance.

Reforms are also needed to ensure that voucher recipients can successfully use their vouchers to secure housing. Despite the evidence that bans on source-of-income discrimination increase the effectiveness of the Housing Choice Voucher program, private landlords are not required to accept HCVs as payment for rent. Congress should enact the “Fair Housing Improvement Act of 2023” (“S.1267”; “H.R.2846”), which would expand federal fair housing protections to prohibit discrimination based on source of income and military and veteran status.

Refundable tax credits can also help millions of cost-burdened renters who are eligible for federal assistance but do not receive it due to inadequate federal funding. The “Rent Relief Act” (“H.R.6721”), for example, would help bridge the widening gap between incomes and housing costs by providing an income-based refundable tax credit for cost-burdened renters who must make impossible choices between paying rent and meeting their other basic needs. The refundable credit covers a percentage of the difference between 30% of income and rent based on income level, with credits covering 100% of the difference between 30% of income and rent for the lowest-income renters.

While long-term solutions are necessary to remedy the persistent shortage of affordable and available housing, short-term assistance is critical for lifting up low-income households and protecting their housing stability when they experience unexpected financial shocks. The “Eviction Crisis Act” (“S.2182” and “H.R.8237” in the 117th Congress) would establish a national housing stabilization fund for renters facing temporary financial setbacks. Stopgap funding for renters in need would help prevent the many negative consequences associated with evictions and homelessness, including mental stress, loss of possessions, instability for children, and increased difficulty finding a new apartment.