-

IDEAS

Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Anti-racism, and Systems-thinking (IDEAS) is the future of housing. It is how together we will build a racially and socially equitable society where everyone has a quality, accessible, and affordable home.

When all people have accessible and affordable homes in diverse and inclusive communities, we all benefit. Our economy benefits. Research shows that housing influences outcomes across many sectors. Students do better in school when they live in stable, affordable homes. People are healthier and can more readily escape poverty and homelessness. Yet, people of color are significantly more likely than white people to face systemic barriers to quality, accessible, and affordable homes.

Housing is the pathway to economic mobility and opportunity. Yet for far too many people in this country, the pathway is full of roadblocks.

In an effort to remove these roadblocks, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) has undertaken an organization-wide initiative to advance racial equity and inclusion in our policy analysis and strategy, our internal operations and relationships, and our work with external partners.

Here are just a few of our IDEAS for making homes happen.

Inclusion |

The act of creating environments in which any individual or group can be and feel welcomed, respected, supported, and valued to fully participate and bring their full, authentic selves to work. An inclusive and welcoming climate embraces differences and offers respect in the words/actions/ thoughts of all people. “Diversity & Inclusion Definitions,” University of Manitoba: Human Resources Diversity & Inclusion, 2017.

Authentic and Empowered Participation

- Invite communities of color and those with marginalized identities to participate on advisory boards and stakeholder groups that provide guidance on NLIHC's policy and programming priorities

- Reestablish NLIHC’s Policy Advisory Committee meetings

- Intensify our engagement of tenant and community leaders—providing opportunities for these leaders to provide significant input into the development of NLIHC’s tenant engagement initiatives

- Host IDEAS listening sessions with members

- Continue including all regions, including the South, in our advocacy

- Include the stories of people with lived expertise into policy and research materials, while being mindful of not falling into stereotypes

- Encourage state partners to invite staff of color from their organization to attend NLIHC meetings to help build their capacity and networking opportunities

Diversity |

Psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among any and all individuals; including but not limited to race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, socioeconomic status, education, marital status, language, age, gender, sexual orientation, mental or physical ability, and learning styles. “Glossary of Terms - Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Resource Page,” Sierra Club Diversity Resource Page, accessed April 20, 2018.

Presence of All Identities

- Build the capacity of partners and advocates to do IDEAS work

- Establish a Racial Equity Working Group for members and partners to share ideas and best practices for increasing diversity and addressing racial equity in their organizations

- Proactively work with organizations advocating on behalf of and serving communities of color

- Ensure racial diversity at all NLIHC events

Equity |

The guarantee of fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement while at the same time striving to identify and eliminate barriers that have prevented the full participation of some groups. The principle of equity acknowledges that there are historically underserved and underrepresented populations, and that fairness regarding these unbalanced conditions is needed to assist equality in the provision of effective opportunities to all groups. “Diversity & Inclusion Definitions,” University of Manitoba: Human Resources Diversity & Inclusion, 2017.

Process of Removing Barriers to Resources and Opportunities

- Raise awareness of racial inequities - and solutions - in every external-facing document and communications

- Help direct media inquiries/speaking opportunities to advocacy organizations led by people of color

Anti-racism |

Opposition to institutional and systemic policies and practices that perpetuate racist beliefs and outcomes. Khalil Girbran Muhammad

Active Process of Confronting Racial Inequalities

- Ensure our policy positions address racial equity and other measures to address the needs of marginalized people

- Speak publicly and honestly about how institutions and policymakers have failed to address racial equity and how we can all improve

- Invest in Black-led social change efforts and partner with Black-led organizations

Systems-thinking |

Systems thinking can help people understand why changes in multiple sectors are necessary to make genuinely sustainable progress towards racial equity in particular spheres such as education, health, or economic security. It can thus help identify both entry points for change and links among those entry points. The resources on systems thinking provide entry points for change-makers to consider how to make progress around racial equity in education, health, and housing, for example, identifying interventions that address the root causes. Racial Equity Tools

Understanding the Cumulative Effects of Seemingly Independent Factors

- Build on and expand existing series of public-facing conversations with racial justice experts to create focused, framing conversations as a team

- Develop an inclusion, diversity, equity, antiracism, and systems-thinking (IDEAS) curriculum for staff and partners

- Highlight reforms needed to ensure policy solutions address racial inequities; Highlight racial disparities, the fact that these disparities are the result of racist federal policy choices, and provide some possible solutions

-

Systems

Social Identities

Social identities reflect how we see ourselves and how others see us. Our social identities are sometimes obvious and clear, sometimes not obvious and unclear, often self-claimed and frequently ascribed by others. Some identities are fluid and change over time.

Examples of social identities are:

- race/ethnicity

- gender

- social class/socioeconomic status

- sexual orientation

- (dis)abilities

- religion/religious beliefs

- tribal or indigenous affiliation

Intersectionality

Intersectionality in its simplest term, is the theory that all oppression is linked. The theory, coined in 1989 by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw is a theory that various forms of discrimination centered on race, gender, class, disability, sexuality, and other forms of identity, do not work independently but interact to produce particularized forms of social oppression. As such, oppression is the result of intersecting forms of exclusionary practices. It is thus suggested that the study of identity-based discrimination needs to identify and take account of these intersectionalities. (Oxford Reference)

Systems of Oppression

There is no hierarchy of oppressions. Audre Lorde

Oppression is the use of power to disempower, marginalize, silence or otherwise subordinate one social group or category, often in order to further empower and/or privilege the oppressor. (The Anti-Oppression Network)Structural Racialization

Understanding Structural Racialization

When talking about racism, most people tend to focus on individual beliefs, biases, and actions. However, it is so much more. Understanding that racism exists not simply in individuals, but “[in] our societal organization and understandings,” is key to being able to develop strategies and solutions to combat it (Calmore, 1998). Our practices, cultural norms and institutional arrangements help create and maintain racialized outcomes.

Structural racialization (also referred to as structural racism) “is a set of processes that may generate disparities or depress life outcomes without any racist actors” (powell, 2013). A structural framing allows us to “take the focus off intent, and even off conscious attitudes and beliefs, and instead turn our focus to interventions that acknowledge that systems and structures are either supporting positive outcomes or hindering them” (powell, 2013). The structural model helps us to understand how housing, education, transportation, employment and other “systems interact to produce racialized outcomes” (powell, 2007-2008). It also helps us to “show how all groups are interconnected and how structures shape life chances” (powell 2007-2008).Discriminatory Housing Policy & Practices

Understanding the History of Discriminatory Housing Policies and Practices

Decades of racial discrimination by real estate agents, banks and insurers, and the federal government made homeownership difficult to obtain for people of color, and those disadvantages have compounded over time. Many factors kept people of color from being able to purchase homes through the middle of the twentieth century: pervasive refusal of whites to live in racially integrated neighborhoods, physical violence to people of color who tried to integrate (often tolerated by the police), restrictive covenants forbidding sales to minorities (some of which were mandated by the Federal Housing Administration), and federal housing policy that denied borrowers access to credit in minority neighborhoods (Rothstein, 2017; Coates, 2014).

The prohibition of racially restrictive covenants and racial discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing has not rectified the inequalities they created. People of color have not benefited over time from the appreciation in the value of the homes they were barred from purchasing, which has expanded the wealth gap and magnified inequalities of opportunity.Racial Disparities in Wealth

Housing discrimination plays a role in explaining the profound racial disparities in wealth that exist today—the wealth of the median white family is 12 times larger than the wealth of the median Black family (Jones, 2017). In a vicious cycle, the wealth gap makes it harder for minority households to invest in homeownership or help their children purchase homes.

Subtler Forms of Housing Discrimination

While overt discrimination was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act, subtler forms of housing discrimination continue to constrain the options of people of color. Undercover testing on Long Island from 2016 to 2019 found evidence that real estate agents still steer minority homebuyers away from white neighborhoods, avoid business in minority neighborhoods, impose more stringent conditions on minority buyers, and engage in other forms of disparate treatment (Choi, Dedman, Herbert, & Winslow, 2019). HUD’s fair housing test in 28 metropolitan areas across the country found that Black homebuyers were shown 17.7% fewer homes than white homebuyers with the same qualifications and preferences (HUD, 2013). Today’s credit scoring system and lending practices also continue to serve as barriers to minority homeownership (Rice & Swesnik, 2012; Bartlett, Morse, Stanton, & Wallace, 2018).

Racial Disparities in Income

Racial disparities in income are the result of discrimination in hiring and setting wages, differences in employment rates, and other factors. A recent review of discrimination studies found that hiring discrimination continues to adversely affect people of color. Whites receive on average 36% more callbacks than Blacks and 24% more than Latinos (Quillian, Pager, Hexel, & Midtbøen, 2017). The same review found no decline in hiring discrimination against Blacks over the past 25 years. Recent wage growth has been racially unequal even for people of the same education. Between 2015 and 2019, white workers with bachelor’s degrees have seen their wages increase by 6.6%, but Black workers with the same degrees have seen their wages decline by 0.3% (Gould & Wilson, 2019). Black workers are more likely than white workers to be underemployed or unemployed at all education levels (Williams & Wilson, 2019). In 2018, the median income of Black and Hispanic households was 61% and 76% of the median white household, respectively (Guzman, 2019).

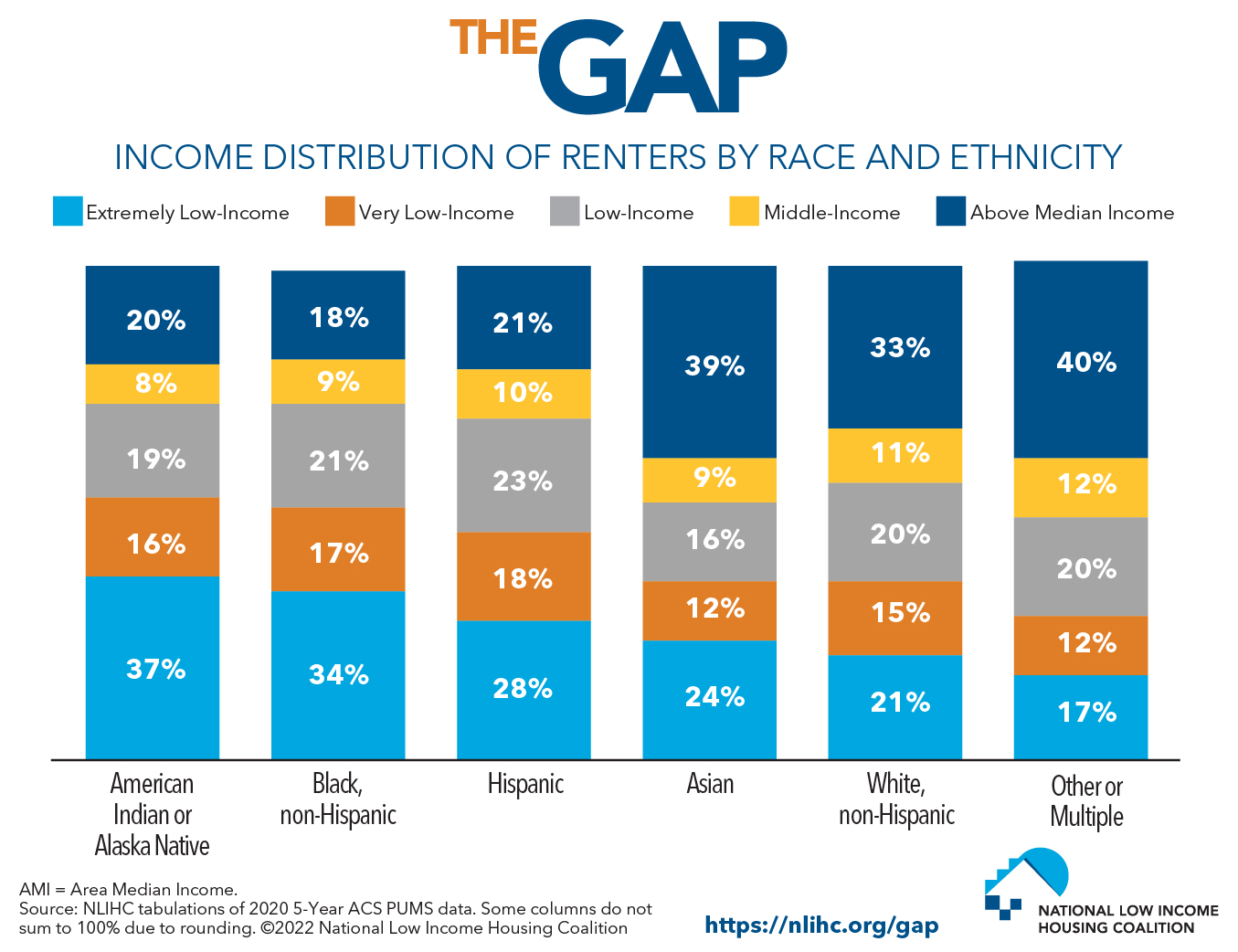

Racial Inequality Among Renters with Extremely Low Incomes

The shortage of affordable and available rental homes disproportionately affects Black, Latino, and Indigenous households, as these households are both more likely to be renters and to have extremely low incomes. Black households are more than three times and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native households more than twice as likely as white households to be extremely low-income renters. For example:

- 57% of Black households are renters, and 19% are extremely low-income renters.

- 52% of Latino households are renters, and 13% are extremely low-income renters.

- In contrast, 27% of white households are renters, and 6% are extremely low-income renters

(See The Gap).

-

Housing Disparities

Persistent Housing Disparities

The orchestrated displacement, exclusion, and segregation of people of color by the United States government have exacerbated racial inequality in the United States. The effects are seen and felt today.

According to NLIHC’s 2024 The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes, systemic racism, both past and present, has left people of color disproportionately likely to be among the lowest-income renters facing a shortage of affordable housing. Black households are more than three times and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native households more than twice as likely as white households to be extremely low-income renters. For example, 57% of Black households are renters, and 19% are extremely low-income renters. Fifty-two percent of Latino households are renters, and 13% are extremely low-income renters. In contrast, 27% of white households are renters, and 6% are extremely low-income renters (Figure 9).

These disparities are the product of historical and ongoing injustices that have systematically disadvantaged people of color, often preventing them from owning a home and significantly limiting wealth accumulation. Some of these injustices persist to this day, including discrimination in both the housing and labor markets. Though many obviously racist institutions and practices, like slavery and de jure segregation, have ended, our society has failed to eliminate discriminatory practices and redress the economic inequalities produced by racist policies.

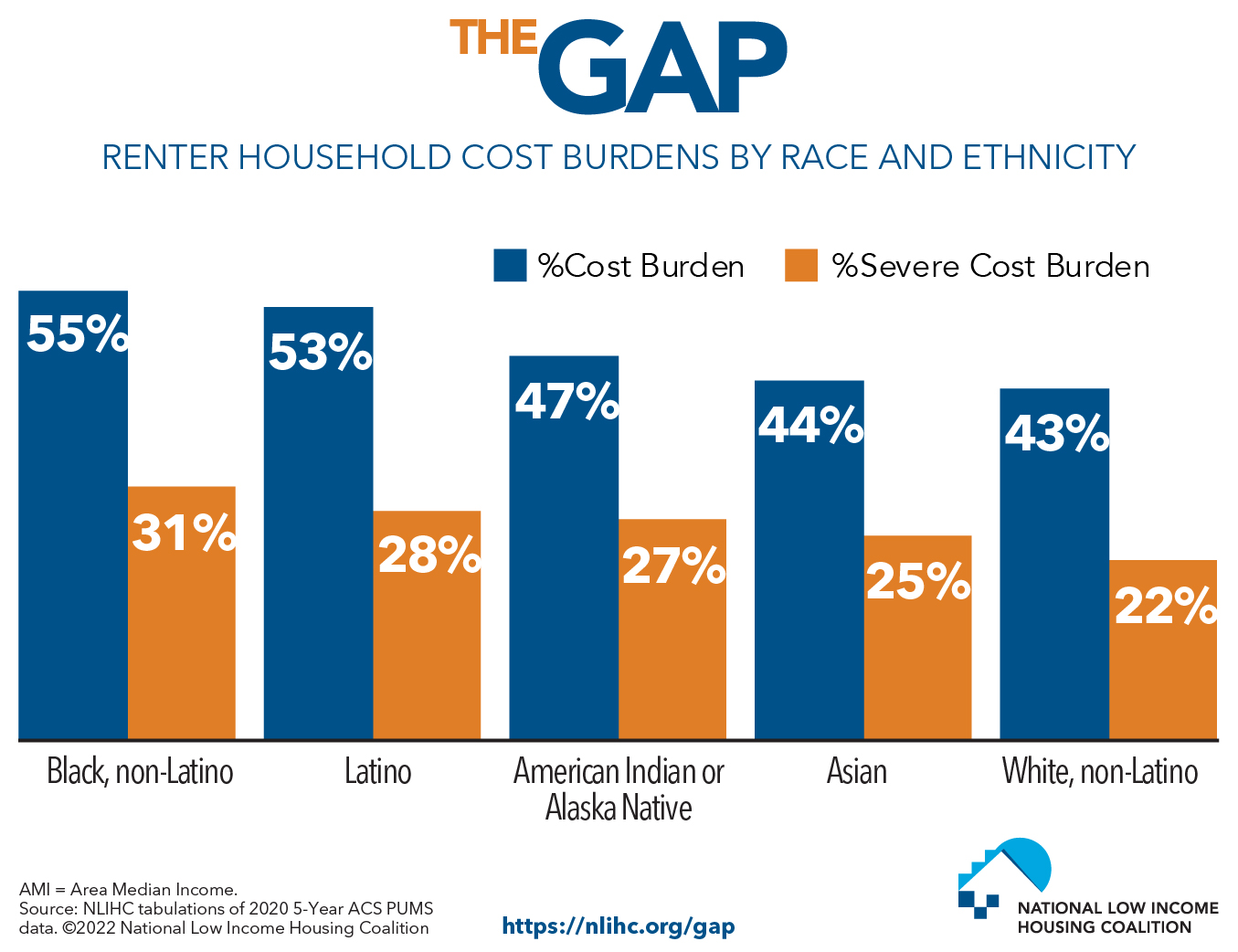

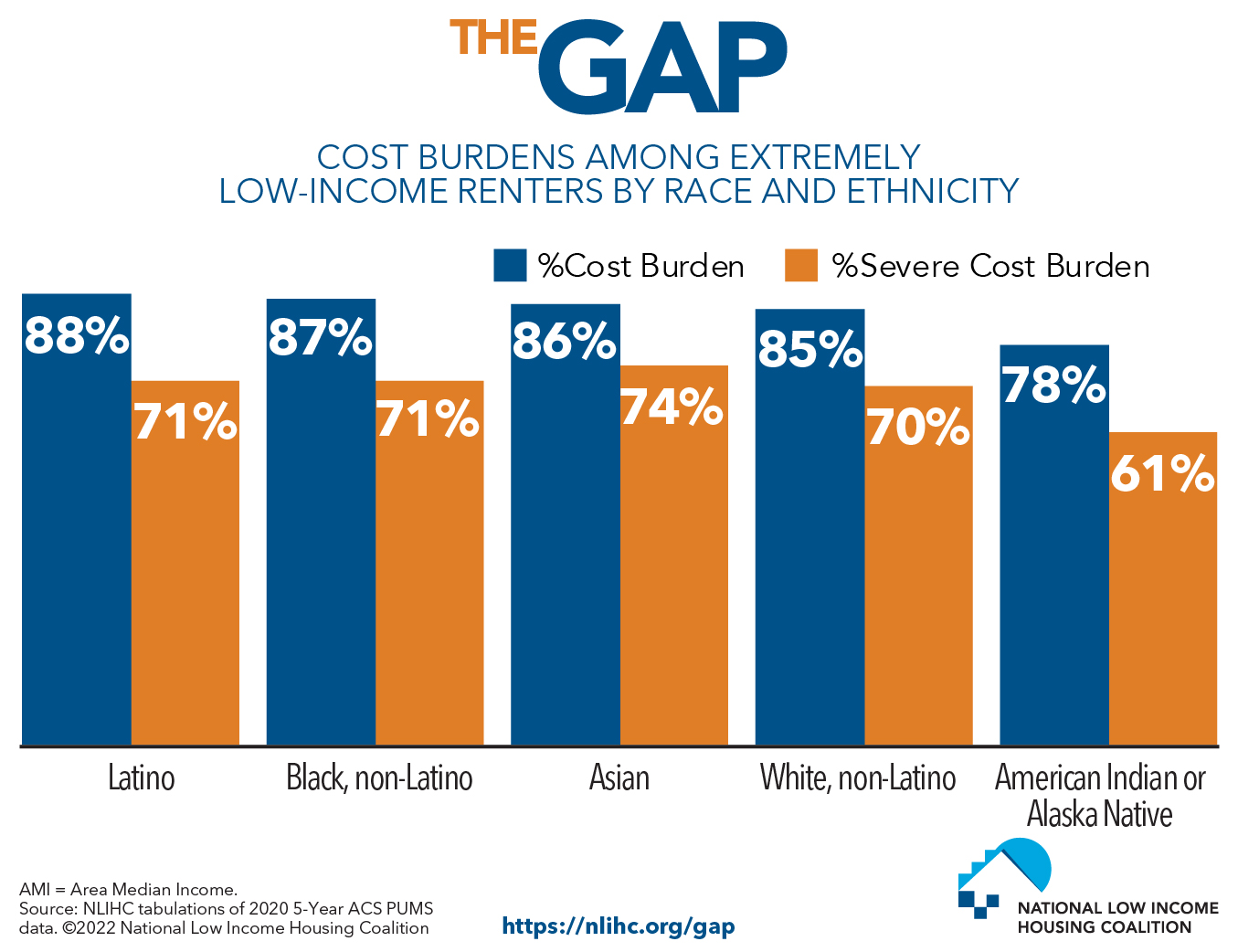

The 2022 ACS data indicate that the median annual incomes of Black ($52,860), Latino ($62,800), and American Indian and Alaska Native ($58,060) households are all significantly lower than the median income of white households ($81,060). These disparities reflect the fact that Black, Latino, and Native American workers are less likely to work in sectors with higher median wages and tend to be paid less than white workers even within the same occupations (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023; Wilson, Miller, & Kassa, 2021; Allard & Brundage, Jr., 2019). Renters of color are more likely to be housing cost-burdened: 56% of Black renters and 53% of Latino renters are housing cost-burdened, compared to 44% of white renters (Figure 10a). One-third of Black renters but only 24% of white renters are severely cost-burdened. Racial disparities in cost burdens can be partially explained by income, as the disparity shrinks when looking only at extremely low-income renters. Extremely low-income renters who are Black, Latino, and white experience housing cost burdens at a rate of 88%, 89%, and 85%, and severe cost burdens at a rate of 75%, 75%, and 73%, respectively (Figure 10b).

Black and Latino renters account for 46% of severely cost-burdened extremely low-income renters. They account for a decreasing share of severely cost-burdened renters with each subsequently higher income level (Figure 11). Because people of color are also more likely than white people to be extremely low-income renters, affordable housing solutions designed to alleviate cost burdens for extremely low-income renters advance racial equity further than solutions that target low- or middle-income renters.

The report argues that Congress must make sustained investments in key HUD and USDA Rural Housing programs to address the underlying systemic shortage of rental homes affordable to the lowest-income renters. These investments should include significant commitments to deeply income-targeted programs such as the national Housing Trust Fund, Housing Choice Vouchers, and public housing.

Read the 2024 edition of The Gap and explore an accompanying interactive map at: www.nlihc.org/gap

Cost Burdens Among Extremely Low-Income Renters by Race and Ethnicity

Racial and ethnic disparities in housing cost burdens tend to be less pronounced among the lowest-income renter households. American Indians and Alaska Natives are less likely to be cost-burdened, but are more likely than others to live in over-crowded or physically inadequate housing.

Download Image: English PDF JPG

-

Tenant Engagement

Tenant Engagement

NLIHC has a deep history of engaging low-income tenants and residents of subsidized housing to inform and advance our policy priorities. For the first 20 years as an organization, NLIHC was governed by a board with a majority of low-income people. The board now represents the breadth of NLIHC members, including six positions set aside for people with very low incomes, and additional avenues for engagement have been created through the years:

- 2010: NLIHC released it’s first Tenant Talk publication, to engage low-income renters in federal advocacy.

- 2013: NLIHC held the first Resident Session, now called the Tenant Session, during the annual Housing Policy Forum. This special session is for low-income tenants to learn how to influence federal housing advocacy and connect with one another.

- 2019: NLIHC hosted its first Tenant Talk Live webinar, providing an opportunity for tenants to connect with NLIHC and one another, learn how to be more involved in influencing federal housing policies, and to share best practices on how to lead in their communities.

- 2022: NLIHC created it’s first Tenant Leader Cohort, now known as The Collective. The Collective is a group of community leaders with lived experience of housing insecurity who work to advance housing and racial justice in their communities.

As NLIHC continues to expand its work with tenant engagement, we encourage tenant leaders to view the content in the tabs above to learn more about the work.

Membership

Tenants and tenant-based organizations are encouraged to become an NLIHC member. Members support the production of publications like Tenant Talk and other NLIHC resources. NLIHC members also have the opportunity to participate in a strong network, to support strategic advocacy for NLIHC’s policy priorities, and to be publicly identified with the affordable housing movement on the national level.

Visit our Tenant Engagement and Resources webpage for more information.

-

Resources

Books, Articles, Podcasts, and More

Need a recommendation on where to start? Start here.

Websites & Tools

- Native Land

- The Structural Racism Remedies Repository, Othering and Belonging Institute

NLIHC Publications

Racial Inequities in Housing, Opportunity Starts at Home

The Gap, NLIHC

Out of Reach, NLIHC

Advancing Racial Equity in Emergency Rental Assistance Programs, NLIHC

NLIHC Partners

- National Racial Equity Working Group: The National Racial Equity Working Group is made up of more than 30 national organizations committed to centering racial equity in the response to homelessness across the United States.

- Rise-Home Stories: Rise-Home Stories is a groundbreaking collaboration between multimedia storytellers and social justice advocates seeking to change our relationship to land, home, and race, by transforming the stories we tell about them.

Federal Government

White House

On January 20, 2021, on his first day in office, President Biden signed an historic Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. It directs the federal government to advance an ambitious equity and racial justice agenda that matches the scale of the challenges and opportunities before us.

The White House held a virtual convening on April 14, 2022, to announce the release of its racial justice and equity plan. More than 90 federal agencies – including all cabinet-level agencies – also released their first-ever Equity Action Plans, as called for by President Biden’s historic Executive Order.

Members of President Biden’s cabinet – including HUD Secretary Marcia L. Fudge – have developed concrete strategies and articulated clear commitments in plans being released by agencies to address the systemic barriers in policies and programs that hold too many people in underserved communities back from prosperity, dignity, and equality.

The equity action plans released by HUD and other agencies will expand federal investments in and support for communities and groups that have been locked out of opportunities for too long, including communities of color, Tribal communities, rural communities, LGBTQI+ communities, disability communities, communities of faith, women and girls, and communities impacted by persistent poverty.

A video of the April 14, 2022 convening can be found here.

Read the complete White House Equity Plans here.

HUD: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released an equity action plan which includes actions to reduce the racial homeownership gap and center equity in the delivery of services to people experiencing homelessness. HUD’s Equity Action Plan emphasizes the ways homelessness is experienced in cities, suburbs, rural areas, and tribal lands; across races and ethnicities; by families and individuals, young and old; and among male, female, transgender, and gender non-conforming people. Even within homeless populations, some groups are less likely to have safe access to homeless shelters, and some are likely to experience homelessness for more extended periods.

Learn more about HUD’s Equity Action Plan here.

USICH: The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) released an equity action plan which focuses on four values – racial equity, Housing First, decriminalization, and inclusion – and identifies several actions that will be undertaken by USICH in pursuit of racial equity, including (1) centering racial equity in its upcoming Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, (2) engaging Tribal nations and re-establishing the Interagency Working Group on Native American Homelessness, and (3) assessing internal USICH policies and employees’ views of racial equity within the organization.

Read the full USICH Equity Action Plan here.

USDA: The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released an equity action plan which establishes an Equity Commission within USDA that will conduct a review and provide recommendations to the Secretary “for how the Department can take action to advance equity.”

See the full USDA Equity Action Plan here.